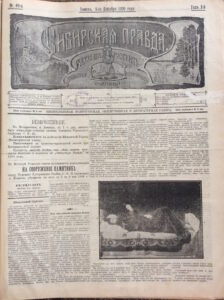

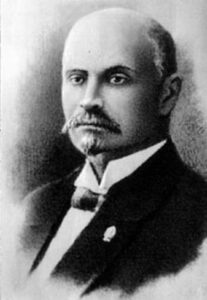

As I delve a bit deeper into the life of Nikolai Klyuev (Kliuev), I’ve become fascinated by his afterlife, the way his life and death became used, politically. Yesterday, I came across a newspaper (Za rodinu) in the on-line St. Petersburg archives from Pskov in 1943 (Nazi occupied territory), that discusses Kliuev as a new poet of the peasantry for the 20th century, highlighting him as a key victim of Bolshevism (the paper claims he died from cold and starvation in Siberia sometime after 1934). I’ve already pointed to the mystery of his death as a key point of discussion during the Glasnost years of the late 1980s. While Kliuev’s death is no longer a mystery, it is fascinating (though not surprising) that one issue not discussed in these pre-1991 accounts of Kliuev was Kliuev’s homosexuality. We now know, as Michael Makin writes, that “Klyuev had fallen victim to Stalinism partly because he was labelled a ‘kulak poet’ and partly because he was denounced as a homosexual.” (p. 58) The timing of his arrest/exile to Siberia couldn’t be clearer, as it occurred just after sodomy was re-criminalized in the Soviet Union.

As I delve a bit deeper into the life of Nikolai Klyuev (Kliuev), I’ve become fascinated by his afterlife, the way his life and death became used, politically. Yesterday, I came across a newspaper (Za rodinu) in the on-line St. Petersburg archives from Pskov in 1943 (Nazi occupied territory), that discusses Kliuev as a new poet of the peasantry for the 20th century, highlighting him as a key victim of Bolshevism (the paper claims he died from cold and starvation in Siberia sometime after 1934). I’ve already pointed to the mystery of his death as a key point of discussion during the Glasnost years of the late 1980s. While Kliuev’s death is no longer a mystery, it is fascinating (though not surprising) that one issue not discussed in these pre-1991 accounts of Kliuev was Kliuev’s homosexuality. We now know, as Michael Makin writes, that “Klyuev had fallen victim to Stalinism partly because he was labelled a ‘kulak poet’ and partly because he was denounced as a homosexual.” (p. 58) The timing of his arrest/exile to Siberia couldn’t be clearer, as it occurred just after sodomy was re-criminalized in the Soviet Union.

Anyway, it is very interesting to see how various political actors (the Nazi occupation regime in 1943 and both liberal- and nationalist-leaning groups in the late-1980s) saw in Kliuev a usable past.

I purchased Vatlin’s book at the recent ASEEES convention in San Francisco, so it is fresh on my mind. Translated and edited by

I purchased Vatlin’s book at the recent ASEEES convention in San Francisco, so it is fresh on my mind. Translated and edited by