One of the more interesting stories in Tomsk in the 1930s was that of poet Nikolai Kliuev (sometimes spelled Klyuev), discussed earlier in this blog.

While I’m still not fully committed to a focus on Kliuev, he draws together some interesting threads from other subjects I’ve been working on in the 44 Lenin Avenue project.

- Memory (part 1): Kliuev’s case was one of the first explored by the Tomsk Memorial Society, according to L.F. Pichurin in his short, 1995 book, Poslednie dni Nikolaia Kliueva (Tomsk: Volodei, 1995). It is the Tomsk Memorial Society, of course, that took over basement 44 Lenin Avenue in 1989 with the purpose of creating a museum. Why was this one of the first cases? Aside from being a well-known poet, there had been a mystery surrounding his death. It was well-known that he had been exiled to the Tomsk region in 1934 and had spent time in both Kolpashevo and Tomsk, but his death remained a mystery until there was archival access in the late-1980s. Reports from the 1960s had stated that he died of a heart attack at a train station on the way back to Moscow. Archival documents, however, confirmed his arrest and execution in 1937.

- Memory (part 2): Kliuev, interestingly, was also subject of an article in the late-1980s in the conservative literary publication, Nash Sovermennik. Iurii Khardikov published some thoughts and re-published some documents pertaining to Kliuev’s time in Tomsk in the 12th issue of the journal from 1989. This publication is noteworthy for the 44 Lenin Avenue project in part because Nash Sovremennik had a slavophile bent, and in some ways fits into some of the ideological debates and discussions that had surrounded the 1909 murder of Ignatii. In Kliuev, we also see early evidence of the memory battles that have played out in post-Soviet Russia, which have seen conservative-nationalist versions of the past pitted against more liberal, human-rights versions (for more on this, see Zuzanna Bogomił’s book, Gulag Memories).

- Russian Literature: In the 1909 murder of Ignatii Dvernitskii, I have discussed the real or imagined role of Dostoevsky. Kliuev, like Dostoevsky, was in some ways a conservative writer (at least from what I understand – I need to do more research!) who saw something distinct and spiritual about the Russian peasantry. This element to Kliuev’s writings is probably the reason for Nash Sovremennik‘s interest in the writer. But it also links Kliuev to another writer, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who was the first official visitor to the Tomsk Memorial Society’s museum at 44 Lenin Avenue in 1994.

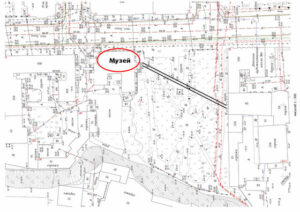

One problem with all of the links to the 44 Lenin Avenue project in the Kliuev story (which is fascinating for a number of other reasons, too, that I won’t explore right now), however, is the lack (so far) of direct evidence that Kliuev spent time at 44 Lenin Avenue. It is likely that he did. The building was, after all, one of two headquarter buildings for the NKVD for the whole period that Kliuev was in Tomsk (1934-37). It also housed an investigative prison in the basement where he could have been incarcerated before his execution. Right now, I’m going through some of these publications pertaining to Kliuev’s time in Tomsk, to see if the building is ever mentioned.

I purchased Vatlin’s book at the recent ASEEES convention in San Francisco, so it is fresh on my mind. Translated and edited by

I purchased Vatlin’s book at the recent ASEEES convention in San Francisco, so it is fresh on my mind. Translated and edited by