Of the questions related to the murder of Ignatii Dvernitskii, many remain unanswered. For example, what was the fate of the two perpetrators, Gerasim Iurinov and Georgii Kuimov? The temporary military tribunal sentenced them to death, commuted to katorga. Katorga was the harshest form of punishment in tsarist Russia, after the death penalty. It generally involved exile and hard labour. Eastern Siberia, particularly the areas in the relative vicinity of Irkutsk, was the main area for katorga punishment in the late-Imperial period. The picture, below, is of katorga prisoners who worked near the Amur River in the Far East, sometime between 1908-1913, and is in the public domain from wikimedia commons.

Continue reading

Page 3 of 4

As should be clear from my posts, one of the key events I’m studying for this project is the murder of the headmaster and monk Ignatii Dvernitskii by two of his pupils in 1909. The case was quickly transferred from the regular courts to a temporary military tribunal, sent from Omsk (The military district court in Omsk covered the military tribunals for all of western Siberia). It was not uncommon, at the time, for especially sensitive cases to be tried by military tribunals, as these courts avoided juries and had less scrutiny. I would love to find the court transcripts of the tribunal for this particular case (took place in October 1909), as such a transcript would be of obvious help in telling the story.

In any case, when I was in Tomsk last summer, I discovered (not surprisingly), that the State Archive of Tomsk Oblast’ did not have the records of the temporary military tribunals. Since then, I’ve been asking around, using connections through friends and colleagues to figure out where these records might be. Could they be in Omsk? Moscow? St. Petersburg? After some back and forth with a colleague at Central European University (CEU) who has many connections with Russian scholars of the pre-revolutionary period, one of these scholars, from Omsk, sent him the following piece of information: “…события гражданской войны привели к массовому уничтожению документов – были разгромлены архивы Акмолинского областного правления, омского военно-окружного суда… уничтожены часть жандармских, полицейских и тюремных архивов” [rough translation: “… the events of the Civil War led to mass destruction of documents: the archives of the Akmolinsk Oblast government [and] the Omsk military district court were destroyed… [also] destroyed were parts of the gendarmerie, police, and prison archives”]. I’m waiting for more information about the source of this information, but the destruction of the Omsk military district court archive likely means that any transcripts or records from the Ignatii Dvernitskii case no longer exist.

Burning of the Akmolinsk District Court

The same CEU colleague sent a photograph from EtoRetro.ru (included in this post) showing the burning of the district court in Akmolinsk. The dates given in the photo are Feb 27-28, but no year is included.

In any case, I’ll keep up the search, but it looks unlikely that I’ll be able to find the court records. Who said hindsight is 20/20?

While at the CAS conference at the end of May, Heather Coleman, expert on the late-Imperial Orthodox Church, pushed me to look more carefully at the role of the Orthodox Church in education in Siberia specifically, since the zemstva (elected local governments that had been established during the Great Reforms), in charge of much of the schooling in European Russia, did not exist in Siberia. Thus, education in Siberia was the responsibility of the church, and those who went to parish schools or who attended the church-teachers’ schools, may not themselves have been religious at all. This lack of religiosity, of course, would have made Ignatii Dvernitskii’s extreme reforms at the school in 1908-09 even more likely to be rejected by many of the pupils, as they may not have been strong believers.

Coleman in passing, however, also stated that she was unfamiliar with the church-teachers’ schools. Indeed, preliminary digging around has given me little background information. A Google search for “церковно учительская школа” is not particularly helpful, as many of the results deal with the church parish schools or the seminaries. The few direct hits, however, show that these schools were not confined only to Siberia. For examples, here’s a link to a brief discussion of one that was founded in Kazan in 1904, and another to a series of photographs from 1909 of a large church-teachers’ school for young women in the heart of the empire, St. Petersburg. The second link, in particular, reveals my ignorance of the subject, as I did not realize that some church parish schools employed women as teachers. JSTOR is unfortunately unhelpful, at least with the search terms I’ve used, as is Project Muse,

Facade of the Women’s Church-Teachers’ School in St. Petersburg, 1909. From: http://humus.livejournal.com/4369090.html

suggesting that English-language scholarship on these types of schools is quite rare. In any case, time to investigate, and if anyone reading this had helpful suggestions, please comment or get in touch!

I’ve included one photograph of the St. Petersburg school (Свято-Владимирская женская церковно-учительская школа (Забалканский пр., 96)), as they do not appear to be copy-protected. Quite impressive!

On June 17, Юрий Черданцев (Iurii Cherdantsev), a former professor at Tomsk Polytechnic University, posted two photos to the public Facebook group, СТАРЫЙ ТОМСК: улочки, дома, судьбы томичей (OLD TOMSK: streets, buildings, lives of Tomsk residents). One was a photo from 17 June 1917, 100 years ago. It depicts a demonstration (one of many during that tumultuous year), organized by the Provisional Government. Our building (on what was then Post Office Street) is visible on the right-hand side of the photograph. The second photo shows roughly the same view in June 2017. I’ve copied and included them, here:

I’m excited to be presenting, “The 1909 Murder of Ignatii Dvernitskii: A microhistorical approach,” as part of a panel on microhistory approaches to Russian and Soviet history at the annual convention of the Canadian Association of Slavists, part of the larger Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences that will take place at Ryerson University later this month. This paper will expand on the paper I presented at the Dostoevsky conference in the Fall, and follow a few of the threads that, I think, show the significance of the murder for understanding late-Tsarist Siberia: education, the press, conservatism, anti-Semitism, Dostoevsky, and student activism.

There are a few aspects of the panel that are particularly exciting for me. Nigel Raab is chairing the panel, and aside from his work on Russia, he is also the author of the recent, Who Is the Historian?, an excellent book on historical methods that I assigned in HIST 3000, “The Historian’s Craft,” here at TRU in Fall 2016. One aspect of the book I particularly like is its emphasis on the research and writing of history as a collaborative process. On that note, I want to give a shout-out to my excellent research assistants (three in 2016-2017, and four in 2015-2016) who have helped me with the 44 Lenina project so far (I won’t mention their names without explicit permission, so perhaps in another post). Their work has been invaluable, particularly related to issues of memory and memorials, the murder of Dvernitskii, and the topics of religion and punishment in the late Tsarist era. One of these assistants even accompanied me for part of my research trip to Tomsk, last summer. While on the collaborative methodology note, it’s also worth emphasizing that none of this would be possible without the work of the archivists, librarians, and museum staff of the Tomsk research venues, as well as the inter-library loan librarians here at TRU. Funding for the entire project has come directly from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), a research grant I would not have won without the help of TRU’s Office of Research and Graduate Studies. And, of course, I’ve received tremendous support from friends, colleagues, and, most importantly, my family. I’m certainly far from alone on this project! Thank you, everyone!

I’m also excited to be presenting with two amazing panelists. Alison Smith is the author of two great books on Imperial Russia, and was the “internal external” reader on my doctoral thesis at the University of Toronto. My approach to the murder of Ignatii is partially inspired by her incredible blog posts on “Russian History Blog,” including the very engaging series on the death of the cheese master. To me, her posts demonstrate the value of microhistorical approaches to Russia’s history. The other panelist, Alan Barenberg, is a long-time friend and fellow Gulag specialist (author of the excellent, Gulag Town, Company Town), whose work and support over the years have meant a tremendous amount to me, and who has definitely made my own work stronger.

On that last note, I’m also very pleased to be part of a roundtable discussion at the CAS titled, “New Directions in Gulag Studies,” chaired by Lynne Viola (my mentor and dissertation advisor), and also including comments from Alan Barenberg, Steve Maddox, and Sean Kinnear. It should be a great conference!

One fun aspect of the 44 Lenina project is that this central part of Tomsk continues to undergo revision, a revision intimately associated with the region’s history. Just a stone’s throw from the building is the main, central square in Tomsk, now a large park with fountains, trees, and several plaques and monuments. This spot had once housed Siberia’s largest cathedral, the Trinity Cathedral, modeled on the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow. Interestingly, although Khabarov (who designed 44 Lenina) was not the cathedral’s main architect, he became the project manager for the cathedral in the 1880s. It took decades to build, and was finally consecrated in 1900. Like the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, Trinity Cathedral was demolished during the early Stalin era.

Trinity Cathedral c. 1898. Image via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Now, the city of Tomsk is considering plans to re-design the square (currently, as in pre-revolutionary times, called “New Cathedral Square”), and there is a movement, as part of this redesign, to have a small chapel built on the site where the cathedral once stood. I’ve linked to a Russian-language report on the issue (“A Chapel on New Cathedral? For and Against“) via Tomsk’s TV2. You can see some photos, at that link, of the designs for the chapel.

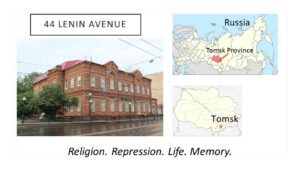

Just a quick update: last Wednesday, as part of TRU’s 2nd Annual Research Week, I presented on the 44 Lenina project as part of the 180s Research Challenge. Based on the popular graduate student 3MT competition, in which each grad student has only 3 minutes to present his or her thesis, using only a static slide and no other props, the 180s Challenge does the same, except for faculty. Thirteen of us presented, on topics ranging from internet dating to “superhero” bacteria in caves. We were judged by TRU’s grad student winners. Nina Johnson‘s presentation, on using labyrinths to reduce stress in the classroom, won the competition. The whole event was great fun, and a wonderful way to get a snapshot of some of the research conducted at TRU: my thanks to the TRU Research Mentors and to TRU’s Office of Research and Graduate Studies, for organizing the event. Below is my introduction slide (basic info: format was the same for everyone) and my static slide from the competition. (Note that the photograph of 44 Lenin Avenue is my own, taken in August 2016, while the maps are modified, public domain maps, licensed through Wikimedia’s Creative Commons.)

The Tomsk Local-Studies Museum (right across the street from 44 Lenin Avenue) has put together an on-line exhibition of photographs of Tomsk from the “February” Revolution of 1917, when Tsar Nicholas II was overthrown. There are many fascinating photographs, mostly street scenes of crowds and demonstrations. Since many demonstrations took place in the New Cathedral Square (diagonally across from 44 Lenina), many of the photographs include the cathedral, which is certainly an impressive structure.

Good news on the “Stone of Sorrow” that was vandalized back in November. At first, police had reported that there was nothing they could do, because the stone wasn’t an officially designated monument, despite the years of ceremonies and the consecration of the monument in 1992. This decision had the staff of the NKVD Remand Prison Museum at 44 Lenin Avenue worried that anyone would be able to do whatever they wanted to the stone. Reports from yesterday, however, state that public pressure has had a positive effect: the stone has been labelled an object of cultural heritage: in other words, a monument that cannot be vandalized without repercussion.

Below is a photo I took of the stone with my phone, Summer 2016.

Sorrow Stone dedicated to the victims of Bolshevik Terror

As touched on in several earlier posts (e.g. here and here), the building at 44 Lenin Avenue, from its humble beginnings as a church-parish school to its role as local NKVD headquarters to its transformation into commercial and commemorative space itself provides a compelling story. This story runs parallel to many of the main trends of Siberia and Russia’s tumultuous 20th century. For the early years and the later years of the building, the specific microhistory stories are themselves rather obvious. For example, the construction of the building connects to threads of education, religion, architecture, and Tomsk’s role in the Russian empire. The architect, V. V. Khabarov, was involved in numerous other projects–including the construction of the enormous Trinity Cathedral a stone’s throw from the parish school–that helped make Tomsk Siberia’s capital in the late-Tsarist period. Another compelling story is the 1909 murder of the school headmaster. In more recent years, the founding of the Memorial NKVD Remand Prison Museum, or the visit of Solzhenitsyn to the building in 1994, also make compelling stories related to post-Soviet reckoning with Stalinist repression.

Nikolai Klyuev. Photo via Wikimedia commons. Public domain.

Even though the building’s infamy today largely derives from its role as local NKVD headquarters and remand prison during the height of Stalin-era repression, finding a specific, compelling story is proving somewhat difficult. Several famous prisoners spent time there, including philosopher Gustav Shpet and poet Nikolai Klyuev. It is even quite possible authorities shot Kluev in the basement of the building, or in the underground passageway underneath the building’s small square. So, the story could move to biography at this point. Several NKVD bosses who spent time in Tomsk achieved infamy either there or elsewhere, including Ivan Ovchinnikov (the “local Beria”), Ian Krauze (better known for his NKVD work in Leningrad), and Ivan Maltsev. The stories linked to the building seem so male dominated (the basement murder, Solzhenitsyn’s visit, and so on), and biographical stories related to the building during its NKVD incarnation risk continuing a trend. In any case, as a historian, it is my job to find a story that is both compelling but also representative, or, perhaps, exceptional, but exceptional in a way that leads to important information and analysis of the time in question. I wonder what NKVD stories will fall along these lines?